From: mongabay.com

The promotional efforts ahead of the upcoming release of the film Crude have helped raise awareness of the plight of thousands of Ecuadorians who have suffered from environmental damages wrought by oil companies. But while Crude focuses on the relatively recent history of oil development in the Ecuadorean Amazon (specifically the fallout from Texaco's operations during 1968-1992), conflict between oil companies and indigenous forest dwellers dates back to the 1940s.

A new paper, published in Environmental Research Letters, details this history, starting before the end of the second world war when Shell Oil entered indigenous territory controlled by the fierce Waorani tribe. Shell didn't fare well in its efforts to exploit the region's rich oil deposits. Two attacks by the Waorani, which left several Shell workers dead, led the oil giant to abandon operations in 1950.

A subsequent attempt to resume oil exploration in the early 1970s was again thwarted by indigenous attacks, this time by the Tagaeri, a tribe that was then, and remains, more reclusive than the Waorani. Ecuador responded by creating Yasuní National Park in 1979. But the battle was far from over.

In the 1980s Ecuador began leasing out blocks of Yasuni to oil companies, while creating a small indigenous reserve for the Waorani, the first time the tribe had direct title to their ancestral land. But the gesture wasn't enough. In the mid-1980s, the Waorani's warrior-cousins, the Tagaeri again launched attacks on oil workers and missionaries trespassing on their traditional lands.

Nevertheless the Ecuadorean government continued to promote oil development in the region, altering the borders of Yasuni to accommodate exploration. From 1992-1995 Maxus Energy Corporation of Dallas (no longer in existence as an independent entity) constructed a new oil access road into Yasuní National Park and Waorani Reserve. Additional access roads were launched by Occidental Petroleum (in 2000) and Petrobras (in 2005), spurring attacks and protests by tribes, including the Waorani and Taromenane, as well as condemnation by increasingly vocal environmental groups. These protests, coupled with a populist movement that triggered a sharp political shift, began to turn the tide. In 2007 President Correa unveiled an ambitious effort to seek funding from rich nations for permanently protecting Yasuni, thereby leaving its oil in the ground. In 2008 Ecuadorians approved a new constitution which recognized the

Nevertheless the Ecuadorean government continued to promote oil development in the region, altering the borders of Yasuni to accommodate exploration. From 1992-1995 Maxus Energy Corporation of Dallas (no longer in existence as an independent entity) constructed a new oil access road into Yasuní National Park and Waorani Reserve. Additional access roads were launched by Occidental Petroleum (in 2000) and Petrobras (in 2005), spurring attacks and protests by tribes, including the Waorani and Taromenane, as well as condemnation by increasingly vocal environmental groups. These protests, coupled with a populist movement that triggered a sharp political shift, began to turn the tide. In 2007 President Correa unveiled an ambitious effort to seek funding from rich nations for permanently protecting Yasuni, thereby leaving its oil in the ground. In 2008 Ecuadorians approved a new constitution which recognized the  rights of indigenous people as well as Pachamama, or Mother Earth. In 2009 Germany agreed to front $650 million for Correa's forest conservation scheme, hoping that by simultaneously protecting Yasuni's forests and avoiding emissions from the burning of its oil reserves, the initiative would help fight climate change. Of course the plan could do more than that. It could deliver to tribes in the Ecuadorian Amazon what they have long sought: an end to encroachment by developers.

rights of indigenous people as well as Pachamama, or Mother Earth. In 2009 Germany agreed to front $650 million for Correa's forest conservation scheme, hoping that by simultaneously protecting Yasuni's forests and avoiding emissions from the burning of its oil reserves, the initiative would help fight climate change. Of course the plan could do more than that. It could deliver to tribes in the Ecuadorian Amazon what they have long sought: an end to encroachment by developers.Matt Finer, Varsha Vijay, Fernando Ponce, Clinton N Jenkins, and Ted R Kahn. Ecuador's Yasuní Biosphere Reserve: a brief modern history and conservation challenges. Environ. Res. Lett. 4 (July-September 2009) 034005 doi:10.1088/1748-9326/4/3/034005

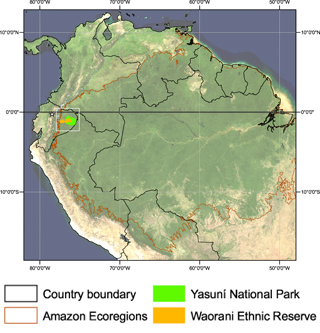

(Image 1: General location of the Yasuní Biosphere Reserve. The reserve, which is composed of Yasuní National Park and the Waorani Ethnic Reserve, is uniquely located at the intersection of the Amazon, Andes mountains, and the equator.

Image 2: Overlapping designations of the Yasuní region. Captions and images courtesy of Finer et. al. (2009).)