Source: mongabay.com

If you have been fortunate enough to visit the Amazon or any other great rainforest, you've probably been wowed by the multitude and diversity of life. However, you also likely quickly realized that the deep jungle is not quite what you may have imagined when you were a child: you don't watch as jaguars wrestle with giant anteaters or anacondas circle prey. Instead life in the Amazon is small: insects, birds, frogs. Even biologists will tell you that you can spend years in the Amazon and never see a single jaguar. Yet rainforest guide and modern day explorer Paul Rosolie says there is another Amazon, one so pristine and with such wild abundance that it seems impossible to imagine if not for Rosolie's stories, photos, and soon videos. This is an Amazon where the big animals—jaguars, tapir, anaconda, giant anteaters, and harpy eagles—are not only abundant but visible. Free from human impact and overhunting, these remote places—off the beaten path of tourists—are growing ever smaller and, according to Rosolie, are in danger of disappearing forever.

"Truly pristine sections of forest in Amazonia are free from any sign of human activity—zero annual river traffic, no trails, trash, chemical pollution, and no machete marks or chopped trees," Rosolie told mongabay.com in a recent interview. In such places, Rosolie has observed that usually elusive animals behave quite differently.

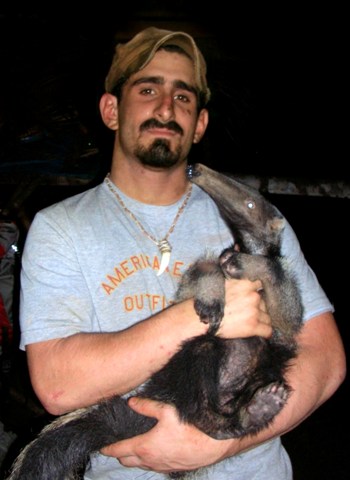

"Animals in truly isolated jungle have no fear of humans. Large herds of peccary are loud and aggressive—the way they should be. The crepuscular habits of the jaguar usually bring it to river’s edge to bask at dawn and dusk. Towering old growth trees surround frequent sightings of giant anteaters, red howler monkeys, macaws, toucans, spider monkeys, capybara, anacondas, tyra, brocket deer, giant armadillo, giant river otter, blue morpho butterflies, the massive black caiman and hundreds of other organisms—it is the most incredible thing on Earth."

"Animals in truly isolated jungle have no fear of humans. Large herds of peccary are loud and aggressive—the way they should be. The crepuscular habits of the jaguar usually bring it to river’s edge to bask at dawn and dusk. Towering old growth trees surround frequent sightings of giant anteaters, red howler monkeys, macaws, toucans, spider monkeys, capybara, anacondas, tyra, brocket deer, giant armadillo, giant river otter, blue morpho butterflies, the massive black caiman and hundreds of other organisms—it is the most incredible thing on Earth."Rosolie says that in Peru, logging, oil, and gold have opened up most of the once wild areas. In addition, some indigenous people and other Amazonian inhabitants are over-hunting to fill a growing market for 'bushmeat' and to sell foreigners trinkets made from killed animals.

"Roads give people access to forests which they then begin to settle, clear, hunt, and log. In the Amazon, thousands of tiny tributaries act as roads, allowing human access. Because of this, humans have gained access into even the most insanely isolated areas of the map," says Rosolie. "This is why a scientist looking for truly pristine area of forest would have to sometimes travel for weeks up a river to reach places where humans do not go. Because of this I feel that the baseline for pristine has become diluted, and we are in danger of forgetting where it really lies."

Rosolie has recently begun carrying a video camera with him during his forays into the deepest jungle areas. In hopes that the resulting footage will help him bring greater awareness to these places and conserve them, he has started the Junglekeeper Project. Already he has succeeded in capturing what may be the longest video ever recorded of the Amazon's least known predator: the short-eared dog (the video is not yet released, but a still from it is at the end of the interview).

According to Rosolie, given that truly wild ecosystems have vanished across much of the world, we have forgotten what natural abundance and natural behavior—especially for targeted species—actually is. Even a place as remote and romantic as the Amazon is in danger of being overridden by human impacts.

"I think we need to develop a new classification for forests that have had NO human activities and where the ecological processes are NOT AT ALL disturbed. Having this classification would help us to identify, discuss, and protect remaining areas of truly pristine, ancient forest," says Rosolie adding that "in megadiverse regions like the Amazon, the Congo, New Guinea, Indonesia and others, being able to distinguish between primary and secondary forest as well as those few remaining places that have escaped all human influence could be a tremendous asset to conservation."

In the interview that follows Rosolie describes his own experiences on a particularly remote and pristine river. It was on this river that Rosolie was once awoken by a jaguar next to him, but it also on this river he learned first hand how quickly an ecosystem can change when poachers arrive.

In an August 2010 interview with mongabay.com, Paul Rosolie talks about what the pristine Amazonian river looks like and what is threatening even the world's most remote places.