Saturday, 18 February 2012

Source:

Business Mirror

RIO DE JANEIRO—An alteration of the relationship between the Amazon rainforest and the billions of cubic meters of water transported by air from the equatorial Atlantic Ocean to the Andes Mountains could endanger the resilience of a biome that is crucial for the global climate, warns a recently concluded two-decade research project.

The Amazon rainforest is a living being that covers an area of 6.5 million sq km, occupying half the territory of Brazil and portions of another eight countries: Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador, French Guiana, Guyana, Peru, Surinam and Venezuela. It is also home to the planet’s largest reserves of freshwater.

In order to more fully understand this complex ecosystem, scientists from Brazil and around the world created the Large-Scale Biosphere-Atmosphere Experiment in Amazonia (LBA).

After 20 years of research, the conclusions reached from the data collected warn of numerous potential threats.

According to the Brazilian National Institute for Space Research (Inpe), one of the agencies participating in the experiment, unless effective policies are implemented in the coming years to reduce greenhouse-gas emissions, by the end of the 21st century there will be 40 percent less rainfall and average temperatures of up to 8 degrees Celsius higher than normal in the Amazon.

This would convert the rainforest into a source of carbon dioxide emissions instead of a “sink” that contributes to carbon sequestration and storage.

The International Energy Agency estimates that in 2010 the world’s population released a record amount of 30.6 gigatons of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, primarily through the burning of fossil fuels.

“The research shows us that the rainforest has a great power of resilience, but also that this power has limits,” physicist Paulo Artaxo, chairman of the LBA International Scientific Steering Committee, told Tierramérica.

“If we continue burning so much carbon, the climate scenario for the region will be considerably unfavorable for any resilience that the rainforest could develop. It would be difficult for it to survive such enormous climate stress,” he added.

To gather data for its research, the LBA used, among other instruments, 13 towers measuring between 40 and 55 meters in height, set up in different points throughout the rainforest to measure the flow of gases, the functioning of basic properties of the ecosystem and many other environmental parameters.

The information collected was analyzed by scientists from various fields in order to understand the rainforest as an interrelated system.

“The perception in the scientific community was that studies carried out in individual disciplines were not sufficiently able to explain the Amazon, and this led to the LBA. It was felt that an integrated effort was needed to explain the rainforest from the viewpoint of the physical, chemical, biological and human sciences, and the relationship between them,” explained Brazilian climate expert Antônio Nobre, another participant in the research initiative.

“When I began my studies in the LBA, my part in the project was mainly about carbon. But carbon without water dries out and the forest catches fire. Without transpiration, there is no carbon sequestration, because there is no photosynthesis. I realized that the water and carbon cycles are inseparable,” Nobre told Tierramérica.

This integrated analysis demonstrated that the Amazon rainforest absorbs a small amount of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, estimated at half a ton per hectare per year.

But the amount of carbon absorbed varies considerably from region to region, depending on environmental alterations. In areas near places where human activity has caused significant degradation, the rate of absorption is reduced, and the Amazon, instead of storing carbon dioxide, is releasing it.

In addition, the rainforest’s absorption of carbon dioxide is counteracted by emissions from deforestation and queimadas, fires intentionally set to clear forested land in order to expand agriculture, stressed Artaxo.

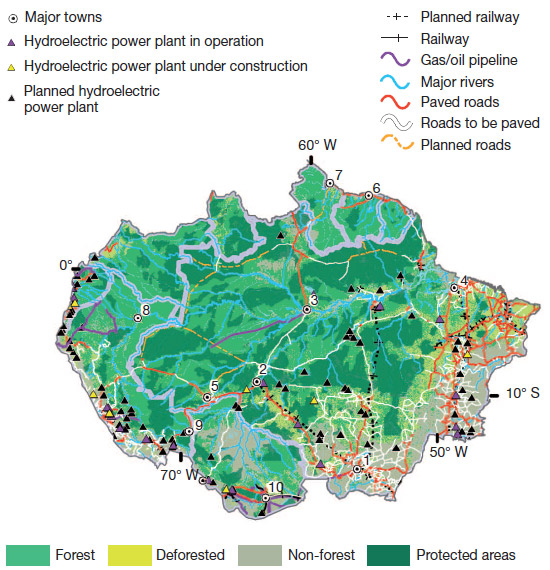

Since the latter practice has declined drastically in recent years, from 27,000 sq km in 2005 to around 7,000 sq km in 2010, “the characteristic feature of the rainforest today is that it absorbs carbon,” he said.

But the changes brought about by the greenhouse effect and rising temperatures in the rainforest have led to a situation where the dry season tends to last longer, creating the conditions for the outbreak of more fires and more carbon dioxide emissions.

“The solid particles released into the atmosphere by queimadas alter the microphysics of clouds and the rainfall regimes,” added Artaxo.

In one of the experiment’s studies, it was observed that the increase in queimadas in the northern state of Rondônia extended the dry season by between two and three weeks, which, in turn increased the incidence of fires and even further aggravated their effect on the functioning of the ecosystem, he explained.

During a very severe drought in 2005, “the Amazon lost a lot of carbon,” he said.

In the event that serious droughts become more frequent, the rainforest could become “an emitter of carbon dioxide and cease to provide an important environmental service,” he warned.

The lengthening of the dry season causes another phenomenon that was also studied in the LBA: the emission of carbon by rivers.

“Small and medium-sized waterways emit significant amounts of gas. This leads to what is called carbon dioxide evasion from bodies of water, and it happens because most of these rivers are saturated with carbon dissolved in their water,” said Artaxo.

As time passes, this carbon “is released into the atmosphere in rather significant quantities. All of the phenomena that alter the Amazon ecosystem have a strong impact on the evasion of gases from the rivers. When the temperature rises, the emission of gases rises as well,” he added.

To illustrate the potential consequences of a lack of equilibrium in the Amazon on the global climate, Nobre referred to the so-called flying-rivers research that begun in the 1970s and was consolidated in the Flying Rivers Project in 2007.

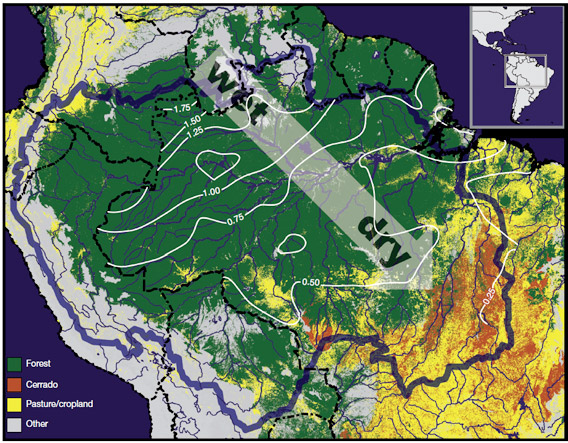

“We discovered that the sun’s action on the equatorial region of the Atlantic Ocean evaporates a large amount of water. This humidity is transported by the wind to the north of Brazil. Around 10 billion cubic meters of water arrive in the Amazon every year in the form of water vapor. Some of it falls as rain, and the rest continues to flow until it runs into the wall of the Andes mountain range,” explained Nobre.

In the Andean region it falls as snow, and when the snow melts, “it feeds the rivers of the Amazon basin. Most of the rain that falls on the rainforest is evaporated again,” he added.

This humidity fluctuates over Bolivia, Paraguay and the Brazilian states of Mato Grosso and Mato Grosso do Sul, in the west, Minas Gerais and São Paulo, in the east and southeast, and even the southern states of Paraná, Santa Catarina and Rio Grande do Sul.

“And it brings most of the rain to all of these regions,” he stressed.

A drought in the Amazon would have a serious impact on these invisible airborne rivers and on the rainfall patterns in these regions, which are very rich in agriculture, Nobre warned.

The LBA is currently a program of the Brazilian Ministry of Science and Technology, coordinated by the National Institute of Amazonian Research, with the support of other agencies.

Its researchers are expanding the initiative into other areas, including agro-pastoral systems and the behavior of carbon dioxide in soybean plantations.

“We have a great deal of work ahead of us to understand the natural processes and the effects of what humans do in terms of the alteration of ecosystems,” Artaxo said.

Bolivia's government has declared a state of emergency in response to flooding caused by heavy seasonal rains.

Bolivia's government has declared a state of emergency in response to flooding caused by heavy seasonal rains.