January 24, 2012

Source:

New York TimesDeforestation in Brazil, driven largely by clearing land for cattle, as in Mato Grosso, above, has lessened. But there has been a shift under President Dilma Rousseff.SÃO PAULO, Brazil — Brazil has made great strides in recent years in slowing Amazon deforestation and showing the world it was serious about protecting the mammoth rain forest.

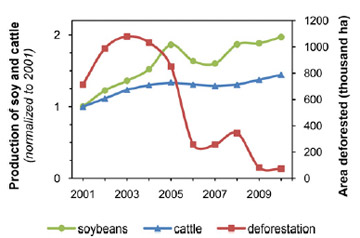

The rate of deforestation fell by 80 percent over the past six years, as the government carved out about 150 million acres for conservation — an area roughly the size of France — and used police raids and other tactics to crack down on illegal deforesters, according to both environmentalists and the government. Brazil’s former environment minister, Marina Silva, became an internationally respected defender of the Amazon. She ran for president in 2010 on the Green Party ticket and won 19.4 percent of the votes.

But since Dilma Rousseff was elected president in late 2010, there have been signs of a shift in the government’s attitude toward the Amazon. A provisional measure now allows the president to decrease the lands already created for conservation. The government is granting more flexibility for large infrastructure projects during the environmental licensing process. And a proposal would give Brazil’s Congress veto power over the recognition of indigenous territories.

“What is happening in Brazil is the biggest backsliding that we could ever imagine with regards to environmental policies,” said Ms. Silva, who now devotes her time to environmental advocacy.

Now, a bill seeking to overhaul the 47-year-old Forest Code, a central piece of environmental legislation, is the most serious test yet of Ms. Rousseff’s stance on the environment.

The debate over the law has revealed the stark disconnect between a population that is increasingly supportive of conserving the Amazon and a Congress in which agricultural interests in the country’s rural north and northeast still hold sway. The furor comes as Brazil is set to hold a United Nations conference on sustainable development in Rio de Janeiro in June.

Before taking office last January, Ms. Rousseff promised to veto any revision of the Forest Code that granted amnesty to landowners who had previously deforested illegally. Then her government negotiated a version of the code, approved by the Senate in December, that would give amnesty to farmers who broke the law before 2008 — provided they agreed to plant new trees. The House is expected to debate the legislation once again in March, with Ms. Rousseff holding final veto power.

The fight over the Forest Code has stoked the age-old struggle over development versus conservation in Brazil, a country that bears the weight of international pressure to protect the Amazon from deforestation because its sheer scale could affect global climatic conditions. Ms. Rousseff, a former energy minister, has so far flashed a more pro-development stance, environmentalists say, shifting the balance from the administration of her predecessor, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, who appointed Ms. Silva.

Agriculture represents 22 percent of Brazil’s gross domestic product. The so-called ruralists in Congress say that the old code is holding back Brazil’s agricultural potential and that it needs updating to allow more land to be opened up to production. Environmentalists counter that there is already enough land available to double production and that the proposed changes would open the door to a surge in deforestation.

Last May, the House approved a more sweeping amnesty for those who had illegally deforested, outraging environmentalists and scientists. It did not help that the deputies refused to receive a group of respected Brazilian scientists that issued a report condemning the changes.

“In the House, there was very little consultation with scientists,” said Carlos Nobre, a scientist at Brazil’s National Institute for Space Research who specializes in climate issues. Still, he said, scientists “waited too long to realize that the House wanted to radically change the Forest Code, creating a broad and unrestricted license to deforest.”

Ms. Silva, who was raised in the Amazon, resigned in 2008 after a backlash by rural governors to restrictions on illegal deforestation she had put in place. But she left what environmentalists consider an effective policy to control Amazon deforestation. Among other tactics, Mr. da Silva’s government used satellite images to home in on deforesters, organized police raids and blacklisted the worst offenders.

“The ruralists have pushed so much to change the Forest Code because the government actually started enforcing it under Marina Silva,” said Stephan Schwartzman, director for tropical forest policy at the Environmental Defense Fund in Washington.

The vote in the House showed how heavily represented the less developed north and northeast are in Brazil’s Congress, a relic of the military dictatorship.

“The skewed proportional representation in Brazil has shown that the environmentalists have much less power in Congress than they have in public opinion,” said Gilberto Câmara, director of the National Institute for Space Research, which monitors Amazon deforestation.

Days after the House vote last May, a poll by Datafolha showed that 85 percent of Brazilians believed the reformed code should prioritize forests and rivers, even if it came at the expense of agricultural production.

After weeks of debate, the bill the Senate approved in December was somewhat more palatable to environmentalists. Rather than outright amnesty for past illegal deforestation, the Senate version lets farmers replant to avoid fines. The legislation now goes back to the House.

“We have to reconcile the generation of income with sustainability,” Izabella Teixeira, the current environment minister, said after the vote.

For Marcos Jank, president of the Brazilian Sugarcane Industry Association, a major reason to change the code is to legalize countless Amazon properties lacking land titles that have complicated the tracking of illegal activity. “When you have a Forest Code that legalizes land titles, then that has the effect of reducing deforestation, not increasing it,” he said.

The government claims the code will reforest about 60 million acres, much of it in the Amazon, which the Environment Ministry calls “the largest reforestation program in the world.” But who will pay for all those new trees? And will the government enforce the replanting requirements?

“The small producers don’t have the money to replant,” Mr. Jank said. “You need to develop programs to help them.”

There are also questions about the size of lands being exempted from the legal requirement to preserve 80 percent of the trees in Amazon properties. The new law would exempt “small” properties of up to four “fiscal modules,” which in the Amazon are almost 1,000 acres combined.

“That is a large property in any part of the world,” Mr. Nobre said. “I see great risk here if this definition is maintained.”

Despite the concerns, there is no denying that deforestation in Brazil, driven largely by clearing land for inefficient cattle grazing, has been on a downward trend. Beyond that, a new generation of satellites over the next two years will give Brazil access to images from seven satellites, up from the current two.

If people abide by the law — a big if — Mr. Câmara and other scientists are predicting that the Brazilian Amazon has a chance by 2020 to become a “carbon sink,” in which the amount of forest being replanted is larger than the amount being deforested.

“President Rousseff is extremely aware of this,” Mr. Câmara said. “When I told her, she almost fell off her chair.”

But to make that happen, “there has to be very strong government financing and support for people to recover the forest,” he said.

Source: guardian.co.uk

Source: guardian.co.uk