Source: mongabay.com

Brazil, which last week moved to reform its Forest Code, may find lessons in Russia's revision of its forest law in 2007, say a pair of Russian scientists.

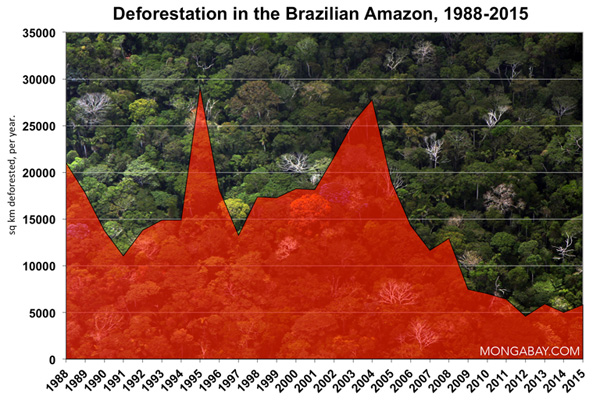

The Brazilian Senate last week passed a bill that would relax some of forest provisions imposed on landowners. Environmentalists blasted the move, arguing that the new Forest Code — provided it is not vetoed by Brazilian President Dilma Rousseff next year — could undermine the country's progress in reducing deforestation.

Based on Russia's recent experience, scientists Victor Gorshkov and Anastassia Makarieva say there may be justification for the concern.

Although one deals with tropical rainforests and the other boreal forests, both nations manage some of the largest forest areas in the world, and one has implemented large-scale changes— Russia— while the other— Brazil— is on the verge of doing so.

At the start of 2007, Russia's new Forest Code went into effect. The new code was meant to move control over forests from federal government to regional governments. Development could now occur without any Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) with forests viewed largely as commodities rather than ecosystems.

"[The] forest code was meant to take power over forest from the old 'owners' (those officials who inherited forest control from the Soviet Union) and give it to the new Russian businessmen who arranged themselves into a force in the end of the 1990s. Members of our present political elite are said to have had shares in some of the largest forest companies in early 90s. Neither the old or the new managers actually cared much about forest conservation, but in comparative terms the old ones were better," Russian scientists Victor Gorshkov and Anastassia Makarieva, who openly opposed the changes, told mongabay.com.

The transition between the old Forest Code and the new one has proven rocky in Russia as many issues were left vague in the new law, allowing what Gorshkov and Makarieva describe as a free-for-all forest policy.

"In practice [the Russian Forest Code] came to mean that everyone could locally log anything without bearing any responsibility about the consequences or sustainability. [...] The chaos that followed when this raw law was adopted caused illegal logging to spike. [...] The North-European Russia was affected most severely, because it has a richer system of roads than say Siberia," Gorshkov and Makarieva say.

"In practice [the Russian Forest Code] came to mean that everyone could locally log anything without bearing any responsibility about the consequences or sustainability. [...] The chaos that followed when this raw law was adopted caused illegal logging to spike. [...] The North-European Russia was affected most severely, because it has a richer system of roads than say Siberia," Gorshkov and Makarieva say.During plans to enact new Forest Code legislation Gorshkov and Makarieva, both with the B.P. Konstantinov Petersburg Nuclear Physics Institute, wrote two open letters to their government "warning against the new forest code." Gorshkov and Makarieva are known as the authors of a revolutionary, and contentious, theory that forests act as a pump for precipitation, bringing rainfall from coastlines to continental interiors. According to them, forests, and not temperatures, drive wind due to condensation. While the theory has received much push-back from some meteorologists, it has also piqued interest among conservationists and other scientists.

In their letters to the government the researchers warned that "enhanced forest exploitation will disrupt the hydrological cycle in the continental Russia and predicted drastic droughts among other climatic extremes."

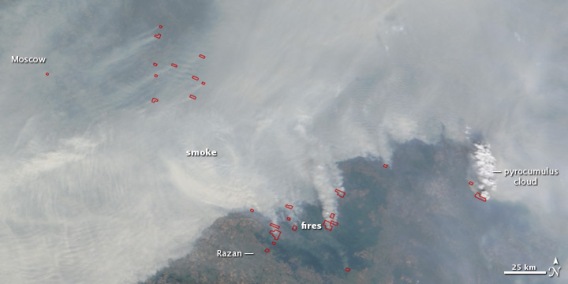

Three years after the implementation of Russia's New Forest Code, record-breaking heatwave, droughts, and fires struck Russia, leaving Moscow under a shroud of smoke, consuming a fifth of Russia's globally-important wheat harvest, and likely killing thousands.

To some it seemed that Gorshkov and Makarieva's warnings had come true, making the two physicists appear like modern-day Cassandras, the always-right Trojan prophetess doomed to be ignore.

"When in 2010 the disastrous heat wave struck the European part of the country, our letters were widely cited in the Russian Internet. We are convinced that the climate anomalies in Europe are due to massive Russian deforestation, which disrupts the normal west-to-east moisture flow from the Atlantic over Eurasia," Gorshkov and Makarieva say.

Still, the causes behind the record heatwave are under debate: two recent studies conflicted over the role climate change may have played in the heatwave and drought.

But one issue that is not contentious is how Russia's new Forest Code undercut fire management during the 2010 disasters. Responsibility for managing forest fires had passed from the federal government to regional governments, yet few had picked up the slack.

"There were no organized bodies to prevent [the fires'] spread. In the result, we lost lives, property and a great forest area was damaged," Gorshkov and Makarieva say.

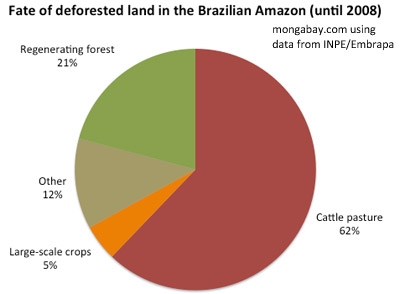

In Russia's case, loosening regulations on forests led to large-scale destruction, a situation that was made worse by a vague law, which made little reference to public and community rights over forests. In addition, people took advantage of the uncertainty to cut down forests for short-term profit. While there specific regulations are different, Brazil this March saw a sudden spike in Amazon deforestation, which many observers have linked to the mere possibility of the new Forest Code becoming law, though deforestation was down in total for the year.

Given Russia's experience, one has to ask, if the new Forest Code should become law, how will Brazil rein-in those who would take advantage over temporary government uncertainty?

A more fundamental question may be: is this the time to loosen regulations in the Amazon or strengthen them? Gorshkov and Makarieva argue through their theory that the on-going loss of the Amazon rainforest will lead to widespread drought, a problem that has already plagued the Amazon in recent years.

"Regarding the consequences of enhanced deforestation for Brazil, the biotic pump concept predicts drastic fluctuations and a growing instability of the hydrological cycle with a trend towards desertification. Recent studies (e.g. Espinoza et al. 2009) confirm the decline of precipitation in the Amazon basin which is particularly well manifested since early 1980. In line with this trend, the Amazon basin saw several outstanding droughts in a short term from 1998 to 2010," they say.

Many environmentalists warn that it could become worse, warning that Brazil's proposed code strips longstanding (even if widely flouted) regulations: WWF estimates that the revised Forest Code will reduce forest cover in Brazil by 76.5 million hectares (295,000 square miles), an area larger than Texas. Such a loss could be devastating for freshwater sources, biodiversity, and indigenous people. But according to Gorshkov and Makarieva it will also exacerbate drought conditions, perhaps undermining the entire Amazon ecosystem and leaving Brazil agriculture high and dry.

Image of Russia and nearby areas from August 4th, 2010 by NASA's Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer during the Russian heatwave in 2010, which sparked drought and fires. Especially intense fires are outlined in red. Smoke from peat and forest fires lead to dangerous levels of pollution throughout Moscow and surrounding areas. Photo by: NASA. Click to enlarge.

Image of Russia and nearby areas from August 4th, 2010 by NASA's Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer during the Russian heatwave in 2010, which sparked drought and fires. Especially intense fires are outlined in red. Smoke from peat and forest fires lead to dangerous levels of pollution throughout Moscow and surrounding areas. Photo by: NASA. Click to enlarge.