Aug 26th 2010

Source:

The Economist

IN A remote corner of Bahia state, in north-eastern Brazil, a vast new farm is springing out of the dry bush. Thirty years ago eucalyptus and pine were planted in this part of the cerrado (Brazil’s savannah). Native shrubs later reclaimed some of it. Now every field tells the story of a transformation. Some have been cut to a litter of tree stumps and scrub; on others, charcoal-makers have moved in to reduce the rootballs to fuel; next, other fields have been levelled and prepared with lime and fertiliser; and some have already been turned into white oceans of cotton. Next season this farm at Jatobá will plant and harvest cotton, soyabeans and maize on 24,000 hectares, 200 times the size of an average farm in Iowa. It will transform a poverty-stricken part of Brazil’s backlands.

Three hundred miles north, in the state of Piauí, the transformation is already complete. Three years ago the Cremaq farm was a failed experiment in growing cashews. Its barns were falling down and the scrub was reasserting its grip. Now the farm—which, like Jatobá, is owned by BrasilAgro, a company that buys and modernises neglected fields—uses radio transmitters to keep track of the weather; runs SAP software; employs 300 people under a gaúcho from southern Brazil; has 200km (124 miles) of new roads criss-crossing the fields; and, at harvest time, resounds to the thunder of lorries which, day and night, carry maize and soya to distant ports. That all this is happening in Piauí—the Timbuktu of Brazil, a remote, somewhat lawless area where the nearest health clinic is half a day’s journey away and most people live off state welfare payments—is nothing short of miraculous.

These two farms on the frontier of Brazilian farming are microcosms of a national change with global implications. In less than 30 years Brazil has turned itself from a food importer into one of the world’s great breadbaskets (see chart 1). It is the first country to have caught up with the traditional “big five” grain exporters (America, Canada, Australia, Argentina and the European Union). It is also the first tropical food-giant; the big five are all temperate producers.

The increase in Brazil’s farm production has been stunning. Between 1996 and 2006 the total value of the country’s crops rose from 23 billion reais ($23 billion) to 108 billion reais, or 365%. Brazil increased its beef exports tenfold in a decade, overtaking Australia as the world’s largest exporter. It has the world’s largest cattle herd after India’s. It is also the world’s largest exporter of poultry, sugar cane and ethanol (see chart 2). Since 1990 its soyabean output has risen from barely 15m tonnes to over 60m. Brazil accounts for about a third of world soyabean exports, second only to America. In 1994 Brazil’s soyabean exports were one-seventh of America’s; now they are six-sevenths. Moreover, Brazil supplies a quarter of the world’s soyabean trade on just 6% of the country’s arable land.

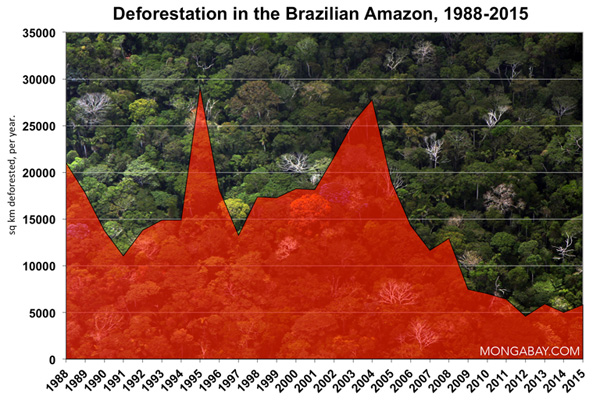

No less astonishingly, Brazil has done all this without much government subsidy. According to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), state support accounted for 5.7% of total farm income in Brazil during 2005-07. That compares with 12% in America, 26% for the OECD average and 29% in the European Union. And Brazil has done it without deforesting the Amazon (though that has happened for other reasons). The great expansion of farmland has taken place 1,000km from the jungle.

How did the country manage this astonishing transformation? The answer to that matters not only to Brazil but also to the rest of the world.

An attractive Brazilian modelBetween now and 2050 the world’s population will rise from 7 billion to 9 billion. Its income is likely to rise by more than that and the total urban population will roughly double, changing diets as well as overall demand because city dwellers tend to eat more meat. The UN’s Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) reckons grain output will have to rise by around half but meat output will have to double by 2050. This will be hard to achieve because, in the past decade, the growth in agricultural yields has stalled and water has become a greater constraint. By one estimate, only 40% of the increase in world grain output now comes from rises in yields and 60% comes from taking more land under cultivation. In the 1960s just a quarter came from more land and three-quarters came from higher yields.

So if you were asked to describe the sort of food producer that will matter most in the next 40 years, you would probably say something like this: one that has boosted output a lot and looks capable of continuing to do so; one with land and water in reserve; one able to sustain a large cattle herd (it does not necessarily have to be efficient, but capable of improvement); one that is productive without massive state subsidies; and maybe one with lots of savannah, since the biggest single agricultural failure in the world during past decades has been tropical Africa, and anything that might help Africans grow more food would be especially valuable. In other words, you would describe Brazil.

Brazil has more spare farmland than any other country (see chart 3). The FAO puts its total potential arable land at over 400m hectares; only 50m is being used. Brazilian official figures put the available land somewhat lower, at 300m hectares. Either way, it is a vast amount. On the FAO’s figures, Brazil has as much spare farmland as the next two countries together (Russia and America). It is often accused of levelling the rainforest to create its farms, but hardly any of this new land lies in Amazonia; most is cerrado.

Brazil also has more water. According to the UN’s World Water Assessment Report of 2009, Brazil has more than 8,000 billion cubic kilometres of renewable water each year, easily more than any other country. Brazil alone (population: 190m) has as much renewable water as the whole of Asia (population: 4 billion). And again, this is not mainly because of the Amazon. Piauí is one of the country’s driest areas but still gets a third more water than America’s corn belt.

Of course, having spare water and spare land is not much good if they are in different places (a problem in much of Africa). But according to BrasilAgro, Brazil has almost as much farmland with more than 975 millimetres of rain each year as the whole of Africa and more than a quarter of all such land in the world.

Since 1996 Brazilian farmers have increased the amount of land under cultivation by a third, mostly in the cerrado. That is quite different from other big farm producers, whose amount of land under the plough has either been flat or (in Europe) falling. And it has increased production by ten times that amount. But the availability of farmland is in fact only a secondary reason for the extraordinary growth in Brazilian agriculture. If you want the primary reason in three words, they are Embrapa, Embrapa, Embrapa.

More food without deforestationEmbrapa is short for Empresa Brasileira de Pesquisa Agropecuária, or the Brazilian Agricultural Research Corporation. It is a public company set up in 1973, in an unusual fit of farsightedness by the country’s then ruling generals. At the time the quadrupling of oil prices was making Brazil’s high levels of agricultural subsidy unaffordable. Mauro Lopes, who supervised the subsidy regime, says he urged the government to give $20 to Embrapa for every $50 it saved by cutting subsidies. It didn’t, but Embrapa did receive enough money to turn itself into the world’s leading tropical-research institution. It does everything from breeding new seeds and cattle, to creating ultra-thin edible wrapping paper for foodstuffs that changes colour when the food goes off, to running a nanotechnology laboratory creating biodegradable ultra-strong fabrics and wound dressings. Its main achievement, however, has been to turn the cerrado green.

When Embrapa started, the cerrado was regarded as unfit for farming. Norman Borlaug, an American plant scientist often called the father of the Green Revolution, told the New York Times that “nobody thought these soils were ever going to be productive.” They seemed too acidic and too poor in nutrients. Embrapa did four things to change that.

First, it poured industrial quantities of lime (pulverised limestone or chalk) onto the soil to reduce levels of acidity. In the late 1990s, 14m-16m tonnes of lime were being spread on Brazilian fields each year, rising to 25m tonnes in 2003 and 2004. This amounts to roughly five tonnes of lime a hectare, sometimes more. At the 20,000-hectare Cremaq farm, 5,000 hulking 30-tonne lorries have disgorged their contents on the fields in the past three years. Embrapa scientists also bred varieties of rhizobium, a bacterium that helps fix nitrogen in legumes and which works especially well in the soil of the cerrado, reducing the need for fertilisers.

So although it is true Brazil has a lot of spare farmland, it did not just have it hanging around, waiting to be ploughed. Embrapa had to create the land, in a sense, or make it fit for farming. Today the cerrado accounts for 70% of Brazil’s farm output and has become the new Midwest. “We changed the paradigm,” says Silvio Crestana, a former head of Embrapa, proudly.

Second, Embrapa went to Africa and brought back a grass called brachiaria. Patient crossbreeding created a variety, called braquiarinha in Brazil, which produced 20-25 tonnes of grass feed per hectare, many times what the native cerrado grass produces and three times the yield in Africa. That meant parts of the cerrado could be turned into pasture, making possible the enormous expansion of Brazil’s beef herd. Thirty years ago it took Brazil four years to raise a bull for slaughter. Now the average time is 18-20 months.

That is not the end of the story. Embrapa has recently begun experiments with genetically modifying brachiaria to produce a larger-leafed variety called braquiarão which promises even bigger increases in forage. This alone will not transform the livestock sector, which remains rather inefficient. Around one-third of improvement to livestock production comes from better breeding of the animals; one-third comes from improved resistance to disease; and only one-third from better feed. But it will clearly help.

Third, and most important, Embrapa turned soyabeans into a tropical crop. Soyabeans are native to north-east Asia (Japan, the Korean peninsular and north-east China). They are a temperate-climate crop, sensitive to temperature changes and requiring four distinct seasons. All other big soyabean producers (notably America and Argentina) have temperate climates. Brazil itself still grows soya in its temperate southern states. But by old-fashioned crossbreeding, Embrapa worked out how to make it also grow in a tropical climate, on the rolling plains of Mato Grosso state and in Goiás on the baking cerrado. More recently, Brazil has also been importing genetically modified soya seeds and is now the world’s second-largest user of GM after the United States. This year Embrapa won approval for its first GM seed.

Embrapa also created varieties of soya that are more tolerant than usual of acid soils (even after the vast application of lime, the cerrado is still somewhat acidic). And it speeded up the plants’ growing period, cutting between eight and 12 weeks off the usual life cycle. These “short cycle” plants have made it possible to grow two crops a year, revolutionising the operation of farms. Farmers used to plant their main crop in September and reap in May or June. Now they can harvest in February instead, leaving enough time for a full second crop before the September planting. This means the “second” crop (once small) has become as large as the first, accounting for a lot of the increases in yields.

Such improvements are continuing. The Cremaq farm could hardly have existed until recently because soya would not grow on this hottest, most acidic of Brazilian backlands. The variety of soya now being planted there did not exist five years ago. Dr Crestana calls this “the genetic transformation of soya”.

Lastly, Embrapa has pioneered and encouraged new operational farm techniques. Brazilian farmers pioneered “no-till” agriculture, in which the soil is not ploughed nor the crop harvested at ground level. Rather, it is cut high on the stalk and the remains of the plant are left to rot into a mat of organic material. Next year’s crop is then planted directly into the mat, retaining more nutrients in the soil. In 1990 Brazilian farmers used no-till farming for 2.6% of their grains; today it is over 50%.

Embrapa’s latest trick is something called forest, agriculture and livestock integration: the fields are used alternately for crops and livestock but threads of trees are also planted in between the fields, where cattle can forage. This, it turns out, is the best means yet devised for rescuing degraded pasture lands. Having spent years increasing production and acreage, Embrapa is now turning to ways of increasing the intensity of land use and of rotating crops and livestock so as to feed more people without cutting down the forest.

Farmers everywhere gripe all the time and Brazilians, needless to say, are no exception. Their biggest complaint concerns transport. The fields of Mato Grosso are 2,000km from the main soyabean port at Paranaguá, which cannot take the largest, most modern ships. So Brazil transports a relatively low-value commodity using the most expensive means, lorries, which are then forced to wait for ages because the docks are clogged.

Partly for that reason, Brazil is not the cheapest place in the world to grow soyabeans (Argentina is, followed by the American Midwest). But it is the cheapest place to plant the next acre. Expanding production in Argentina or America takes you into drier marginal lands which are much more expensive to farm. Expanding in Brazil, in contrast, takes you onto lands pretty much like the ones you just left.

Big is beautifulLike almost every large farming country, Brazil is divided between productive giant operations and inefficient hobby farms. According to Mauro and Ignez Lopes of the Fundacão Getulio Vargas, a university in Rio de Janeiro, half the country’s 5m farms earn less than 10,000 reais a year and produce just 7% of total farm output; 1.6m are large commercial operations which produce 76% of output. Not all family farms are a drain on the economy: much of the poultry production is concentrated among them and they mop up a lot of rural underemployment. But the large farms are vastly more productive.

From the point of view of the rest of the world, however, these faults in Brazilian agriculture do not matter much. The bigger question for them is: can the miracle of the cerrado be exported, especially to Africa, where the good intentions of outsiders have so often shrivelled and died?

There are several reasons to think it can. Brazilian land is like Africa’s: tropical and nutrient-poor. The big difference is that the cerrado gets a decent amount of rain and most of Africa’s savannah does not (the exception is the swathe of southern Africa between Angola and Mozambique).

Brazil imported some of its raw material from other tropical countries in the first place. Brachiaria grass came from Africa. The zebu that formed the basis of Brazil’s nelore cattle herd came from India. In both cases Embrapa’s know-how improved them dramatically. Could they be taken back and improved again? Embrapa has started to do that, though it is early days and so far it is unclear whether the technology retransfer will work.

A third reason for hope is that Embrapa has expertise which others in Africa simply do not have. It has research stations for cassava and sorghum, which are African staples. It also has experience not just in the cerrado but in more arid regions (called the sertão), in jungles and in the vast wetlands on the border with Paraguay and Bolivia. Africa also needs to make better use of similar lands. “Scientifically, it is not difficult to transfer the technology,” reckons Dr Crestana. And the technology transfer is happening at a time when African economies are starting to grow and massive Chinese aid is starting to improve the continent’s famously dire transport system.

Still, a word of caution is in order. Brazil’s agricultural miracle did not happen through a simple technological fix. No magic bullet accounts for it—not even the tropical soyabean, which comes closest. Rather, Embrapa’s was a “system approach”, as its scientists call it: all the interventions worked together. Improving the soil and the new tropical soyabeans were both needed for farming the cerrado; the two together also made possible the changes in farm techniques which have boosted yields further.

Systems are much harder to export than a simple fix. “We went to the US and brought back the whole package [of cutting-edge agriculture in the 1970s],” says Dr Crestana. “That didn’t work and it took us 30 years to create our own. Perhaps Africans will come to Brazil and take back the package from us. Africa is changing. Perhaps it won’t take them so long. We’ll see.” If we see anything like what happened in Brazil itself, feeding the world in 2050 will not look like the uphill struggle it appears to be now.

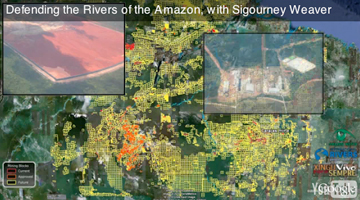

The Belo Monte Dam would be "a disaster for the Xingu River, for the rainforest, and certainly for all the indigenous people and families living along the river," said Weaver, an actress who starred in last year's blockbuster Avatar. "Their way of life will disappear."

The Belo Monte Dam would be "a disaster for the Xingu River, for the rainforest, and certainly for all the indigenous people and families living along the river," said Weaver, an actress who starred in last year's blockbuster Avatar. "Their way of life will disappear." Rebecca Moore of Google Earth Outreach said she hoped the video would lead to more engagement on the issue.

Rebecca Moore of Google Earth Outreach said she hoped the video would lead to more engagement on the issue.